The Fens are a generally unvisited part of East Anglia that lie roughly from the wash southwards down to just beyond the Isle of Ely. In the winter months, the Fens can be dull, misty and murky. They are seemingly quite uninteresting. This is where I live though and recently I had a bit of a prowl round.

Virtually all of the Fen landscape rests at or just below sea level. Everywhere is flat. It has been like this since the beginning of time. The Romans were there first before most other people. In those days, nobody wanted to travel to the Fens because nobody really could. The area was always semi flooded or saturated. Only the few locals wanted to be there because they assumed that the terra firma, such as it was, belonged to them. Any pretentious invaders were dealt with a bit of local, raw and graceless cruelty.

The inhabitants got around the flooded areas by making pole vault sticks out of the indigenous willow trees. The whole terrain was mysterious and scary. Will-o’-the-wisp light flashes would randomly go off fuelled by escaping methane gas pockets. The locals often developed a form of malaria due to the flocks of mosquito like flies. They would fend off the symptoms by consuming vast quantities of alcohol and opium. They lived tough lives and became known as ‘Fen Tigers’. That description of the Fenland people is still used today. I know all about them from my school days.

Fenland however, if dried out, is a piece of the most rich and productive farmland in the whole country. People discovered that they could make money, lots of it, from the land if they played their cards right. To this day they still do. There are a lot of low profile farmers in the region that keep themselves to their very affluent selves tucked away in the corners.

When the Romans first got the Fens, they tried a bit of artificial drainage but did not achieve very much. They all left before too long. The difficulty is that the water cannot drain into the rivers and subsequently on to the sea. Gravity only works for things that need to go downhill. The other problem is that when the Fenland is dried out and the land shrinks, the level drops even more. The resulting rich dried peat however, supports vast quantities of highly nutritious vegetables that can be sold for vast sums of highly nutritious money.

When the Romans first got the Fens, they tried a bit of artificial drainage but did not achieve very much. They all left before too long. The difficulty is that the water cannot drain into the rivers and subsequently on to the sea. Gravity only works for things that need to go downhill. The other problem is that when the Fenland is dried out and the land shrinks, the level drops even more. The resulting rich dried peat however, supports vast quantities of highly nutritious vegetables that can be sold for vast sums of highly nutritious money.

We human beings began to conquer these difficulties in the seventeenth century when some bright spark invented the windmill. The mills would pump the water from the land uphill a bit into the ditches and then into the local rivers that occupied higher land. All would then flow merrily away into the sea. It was a very inefficient, slow and labour intensive process but it sort of worked when the wind blew hard enough. Things got a lot better when the steam engine came along.

The Fenland area covers around 1300 square miles and ultimately around 100 steam pumps were provided to drain it all. The problem is a large one that required imaginative engineering and determination to solve. Heavy rain always makes the difficulties harder to deal with. One inch of rain means that one acre of land is covered by an additional 100 tons of water. When the figures were grossed up, the wide national area of Fenland needed some effective pumping machinery.

Steam has been replaced these days of course, but a pumping steam engine is a fascinating piece of machinery. Some enthusiasts devote their lives to their study. There are now just a few steam pumping houses preserved but generally not in full working order. I went to an original pumping station that has been converted into a drainage museum. It is in the village of Prickwillow, close to the City of Ely. There is also an original, but now defunct, steam pumping engine house near the hamlet of Pymore, also close to Ely. The probable greatest survivor of them all is close to the village of Streatham, a little north of Cambridge. Look for the signpost, ‘Streatham Old Engine’. Another one is not far from Earith, a bit closer to Ely. I went to them all to find out about what life was like for the engine operators in the nineteenth century.

Steam has been replaced these days of course, but a pumping steam engine is a fascinating piece of machinery. Some enthusiasts devote their lives to their study. There are now just a few steam pumping houses preserved but generally not in full working order. I went to an original pumping station that has been converted into a drainage museum. It is in the village of Prickwillow, close to the City of Ely. There is also an original, but now defunct, steam pumping engine house near the hamlet of Pymore, also close to Ely. The probable greatest survivor of them all is close to the village of Streatham, a little north of Cambridge. Look for the signpost, ‘Streatham Old Engine’. Another one is not far from Earith, a bit closer to Ely. I went to them all to find out about what life was like for the engine operators in the nineteenth century.

The one at Streatham was the best. The steam powered engine with all its boilers and tools is still completely intact. Nowadays, the operation is demonstrated by an electric motor probably because the coal is too expensive and maintenance costs too high. But it works still and is a fascinating sight to observe.

I entered the building and was faced by a row of enormous boilers that had burnt the fuel to provide the energy to shift the water. They reminded me of the relics left over at the wartime German concentration camps like the one at Auschwitz. The boilers were left, as they were in Poland, with the doors open displaying bits of fuel debris.

I entered the building and was faced by a row of enormous boilers that had burnt the fuel to provide the energy to shift the water. They reminded me of the relics left over at the wartime German concentration camps like the one at Auschwitz. The boilers were left, as they were in Poland, with the doors open displaying bits of fuel debris.

Streatham contains a vast beam engine that has been carefully preserved. I had to wonder how all of the massive and dense machinery had been transported to this rural outpost. By the river I supposed. The custodian there operated it for me electrically. I watched the vast flywheel rotate and the huge beam well above my head nod gracefully in its timeless fashion. The machinery was driving a scoop wheel in the drain outside to lift the water into the river alongside before eventually flowing out to sea.

During the productive decades of steam drainage, the engine operators were men of mystery. Each engine had its own characteristics and foibles. Someone had to learn them and understand them. They were all a secret to the ‘controller’. The engine man had a job for life.

I learnt about how the engine had to be stopped so that ‘top dead centre’ or ‘top bottom centre on the piston had to be avoided. If this happened, the fly wheel would have to be ‘barred’ away from this position to prevent the machinery from literally blowing itself up on the next start. The ‘barring’ would take some time and would require great strength from the poor person detailed to do it.

I learnt about how the boiler maintenance had to be regularly carried out. The poor chap doing this would have to crawl inside the very confined and still hot innards and dig out and scrape away all the debris. That person would have to strip himself naked afterwards and rub himself down before he dared to return home to his wife.

I learnt about how the boiler maintenance had to be regularly carried out. The poor chap doing this would have to crawl inside the very confined and still hot innards and dig out and scrape away all the debris. That person would have to strip himself naked afterwards and rub himself down before he dared to return home to his wife.

There was so much to see and learn about steam Fenland drainage at Streatham. I began to understand the fascination about steam power that seems to occupy the modern consciousness of so many people these days. The steam engine at Streatham was installed in 1831. It ran, battling the heavy rain, almost faultlessly for about 45000 working hours until it was replaced by yet even more efficient diesel machinery early in the 20th. Century.

The Cambridgeshire village of Prickwillow is named after the ties used on thatched roofs I think. It houses a really super museum these days presenting the history of Fenland drainage. The building used to house one of the nineteenth century steam engines but most of that has gone. The museum exhibits the oil engines or diesel engines that replaced the steam in the 20th. Century.

The Cambridgeshire village of Prickwillow is named after the ties used on thatched roofs I think. It houses a really super museum these days presenting the history of Fenland drainage. The building used to house one of the nineteenth century steam engines but most of that has gone. The museum exhibits the oil engines or diesel engines that replaced the steam in the 20th. Century.

The actual oil engines that productively operated from Prickwillow draining the surrounding Fen country are kept in a beautifully preserved condition in the museum. There is the original Allen T47 and 3S60 engines along with the Allen 3 Cylinder. There is the Lister-Petter 2 Cylinder and 5-J vacuum pump. You will also find the Mirrlees-Bickerton, Tangye and Ruston pumping engines. They are all splendidly presented in polished and painted first class condition for all to see. The entrance fee is only three pounds and you can stay as long as you like.

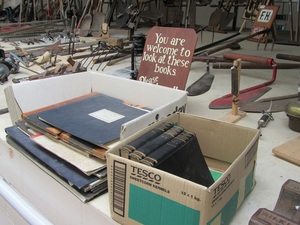

Prickwillow also exhibits many of the older tools and books and artefacts from the days of steam. For visitors having an interest in such early 20th. Century engineering and previous history will be absorbed for hours. I am actually interested in other things but I really enjoyed the atmosphere and rural culture that I sensed in the museum. It was curated and manned by some of the nicest village people who had family connections with local drainage over the centuries that you could hope to find. The museum is run by ‘The Friends of the Prickwillow Drainage Museum’. New supporting members are always welcome.

I went to look too at the old pumping houses at Pymore village (the hundred foot pumping engine) and the one at Earith. Both were locked and inaccessible on the day that I went. I understand that the original steam engine is still housed in its shed in Earith. It is subject to preservation and may run again publically at sometime in the future.

I went to look too at the old pumping houses at Pymore village (the hundred foot pumping engine) and the one at Earith. Both were locked and inaccessible on the day that I went. I understand that the original steam engine is still housed in its shed in Earith. It is subject to preservation and may run again publically at sometime in the future.

The Fens still need to be drained today of course. The operation nowadays runs with semi-automatic, powerful electrical pumps though. They do not take up much space but generally operate at the original pumping locations. In some places, the still serviceable and operable diesel engines act in a standby capacity in the event of a power failure. This is true at Prickwillow and the engine is kept in perfect running order.

Wicken Fen in Cambridgeshire is now the only preserved, undrained part of the Fens. It is preserved for the sake of the unique species of insect life and fauna for research purposes. It is open to the public and is just as the Fenland landscape was before any drainage took place. It is very wet, saturated and muddy but compares so poignantly nowadays with all the rich and productive agricultural land around it. If the pumping engines all fail, we Fen Tigers will get our feet wet.